The 2025 federal election delivered a landslide victory to the Australian Labor Party (ALP), marking a historic moment. This win breaks a long-standing record—it’s the first time since Bob Hawke that an ALP Prime Minister has secured a second term in a federal election. Beyond the numbers, the result reflects a complex yet dynamic geopolitical backdrop.

Many had placed their bets on Donald Trump’s disruptive appeal and unconventional diplomatic playbook, trusting that his business acumen would drive him to push American interests aggressively. Indeed, he fulfilled some of his election promises. However, for many observers, his unpredictability may have been too much to stomach. Australians, having carefully watched the progress of “Making America Great Again,” are left asking: did it truly benefit the American people? Only time will tell, but the economic disruption and market chaos that ensued have left most Australians cautious, if not wary, of adopting a similar model.

The result? A strong national swing to the left.

Social Media Strategy

In this election, political parties made a noticeable push to engage non-English speaking communities, particularly Chinese-Australian voters, by leveraging platforms such as WeChat and RedNote. However, the use of foreign languages in political campaigning revealed a host of challenges—tight timelines and limited budgets often resulted in poorly crafted content. As I browsed through various campaign materials, it became clear which candidates had engaged professionals and which hadn’t.

Does poor translation necessarily mean a failed message? Not always. But automated translations—like those offered by AI chat tools—still struggle to deliver meaning with nuance, especially from English to LOTE. Professional translators have long known this.

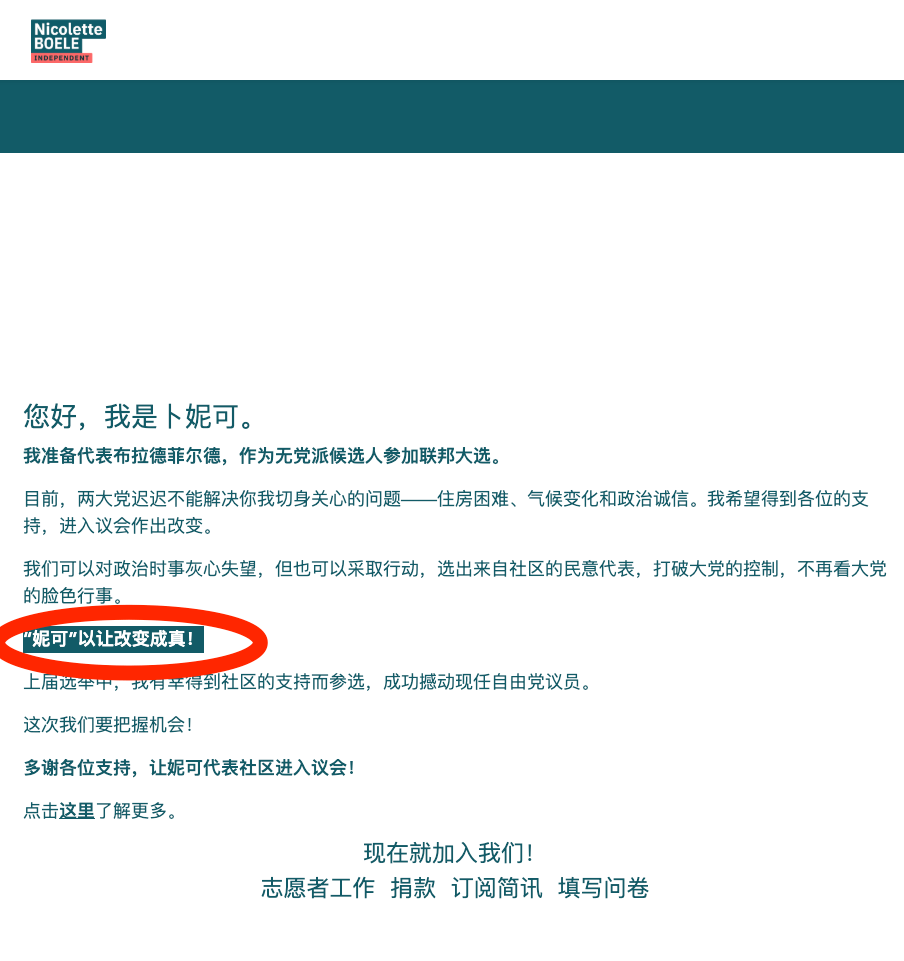

For instance, Nicolette Boele’s Chinese translation broadly conveyed her message, but lacked flow and connection.

Small errors, such as the use of “以 [through/by]” instead of “已 [already/tense marker for the past or perfect tenses]” in “妮可以让改变成真!” [In English with correction – Nicole has made the changes!] —though seemingly minor—can affect the credibility and impact of a campaign.

For Case 2, I believe all Chinese speakers would agree that it needs to be fine-tuned. It follows the English structure too closely, so it doesn’t flow in Chinese. Thus, it sounds rigid and awkward due to syntactic interference, or perhaps lexical calque.

Case 1

“妮可以让改变成真!”

[In English – Nicole has made the changes!]

Case 2

我会无差别地与所有政治派别的议员合作,通过立法帮助所有人,而非政治说客和他们的金主。

[In English – I will work with MPs from all political parties without bias, passing legislation that helps everyone — not political lobbyists and their wealthy backers.]

Some might argue I’m being overly critical and should simply appreciate the increased availability of translated content.

And I’m always grateful — language accessibility is a generous and deeply considerate gesture, no matter the context.

But my point is this: technology can be useful, but it must be complemented by human review. Yes, it adds to the cost—but for something as important as influencing a vote, getting it right is more important than just getting it done.

If the goal is to win votes, then the message must resonate. That usually requires more than just a word-for-word translation. It calls for localisation—a blend of copywriting and cultural insight. Simply translating accurately isn’t enough to inspire trust or action.

Languages are shaped by thousands of years of lived experience, and a few decades of globalisation haven’t changed the deep-rooted mechanisms behind them. Even in today’s anglicised world, language still reflects our unique ways of thinking.

Hypernymy vs Hyponymy

For example, in Chinese, general terms like “羊” (yang) are often used to refer to both sheep and goats, while English prefers to distinguish between the two. Likewise, terms such as “內部章程” encompass concepts like internal rules, articles of association, bylaws, or governance regulations—all of which English separates with distinct terminology.

There isn’t one common English word that perfectly includes both sheep and goats, while ‘bovid’ would involve other species, such as cattle.

But the reverse can also be true. When discussing family roles, Chinese prefers specificity: terms like “younger sister,” “older brother,” “paternal aunt,” or “maternal uncle” are standard. In contrast, English often defaults to the general—simply “sister” or “aunt.”

A simple sentence such as ‘This is my sister’ can be almost untranslatable, without knowing the ages of the speaker and the sister, for a Chinese speaker.

These differences demonstrate that a translation focused solely on linguistic accuracy can often miss cultural authenticity. And when a message lacks authenticity, it risks failing to inspire, failing to connect—and ultimately, failing to persuade.

Is hypernymy versus hyponymy the only factor at play? Certainly not. Translation is complex. Every situation—every context, direction, and language pair—requires tailored consideration.

But one thing is clear: if we want to speak to people, we must speak their language—not just in words, but in meaning.

#AusVotes2025 #PolicyNotPolitics #ALP2025 #LaborLandslide #AnthonyAlbanese #FederalElection2025 #PoliticalStrategy #SocialMediaCampaign #Geopolitics #AustralianPolitics #ElectionAnalysis #PoliticalShift #DigitalCampaigning #YouthVoters #CostOfLiving #RenewableEnergyPolicy #ElectionInsights #PoliticalTrends #VoterEngagement #CampaignStrategy #PoliticalVictory #AustralianLaborParty