India & Pakistan: The Sublime Tragedy of Partition and the Fight for Identity

By 1947, the British Empire was on its last legs in India. After centuries of control, it was now in retreat, exhausted by World War II and pressed by growing demands for independence. Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, arrived with a single task: get Britain out — fast.

But there was one big problem: deepening tensions between Indian nationalists who wanted a united country, and Muslim leaders who feared being politically sidelined in a Hindu-majority nation. The British solution? Partition — to divide the land and create two countries: India and Pakistan.

What followed would change South Asia forever.

The Two-Nation Theory: One Land, Two Peoples

At the heart of Partition was an idea:

Hindus and Muslims are two distinct nations, each deserving their own homeland.

This was the Two-Nation Theory, championed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League. They argued that Muslims would never be safe or fairly represented in a Hindu-majority India. The only answer? A separate nation: Pakistan.

A Patchwork of Identities

But British India wasn’t just Hindus and Muslims. It was home to a mosaic of communities — Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Jews — each with their own beliefs, languages, and homelands. British policies had already deepened divides, often using “divide and rule” tactics to manage the population.

By the 1940s, national tensions had reached a boiling point. Riots were breaking out. Trust was breaking down. The dream of coexistence seemed out of reach.

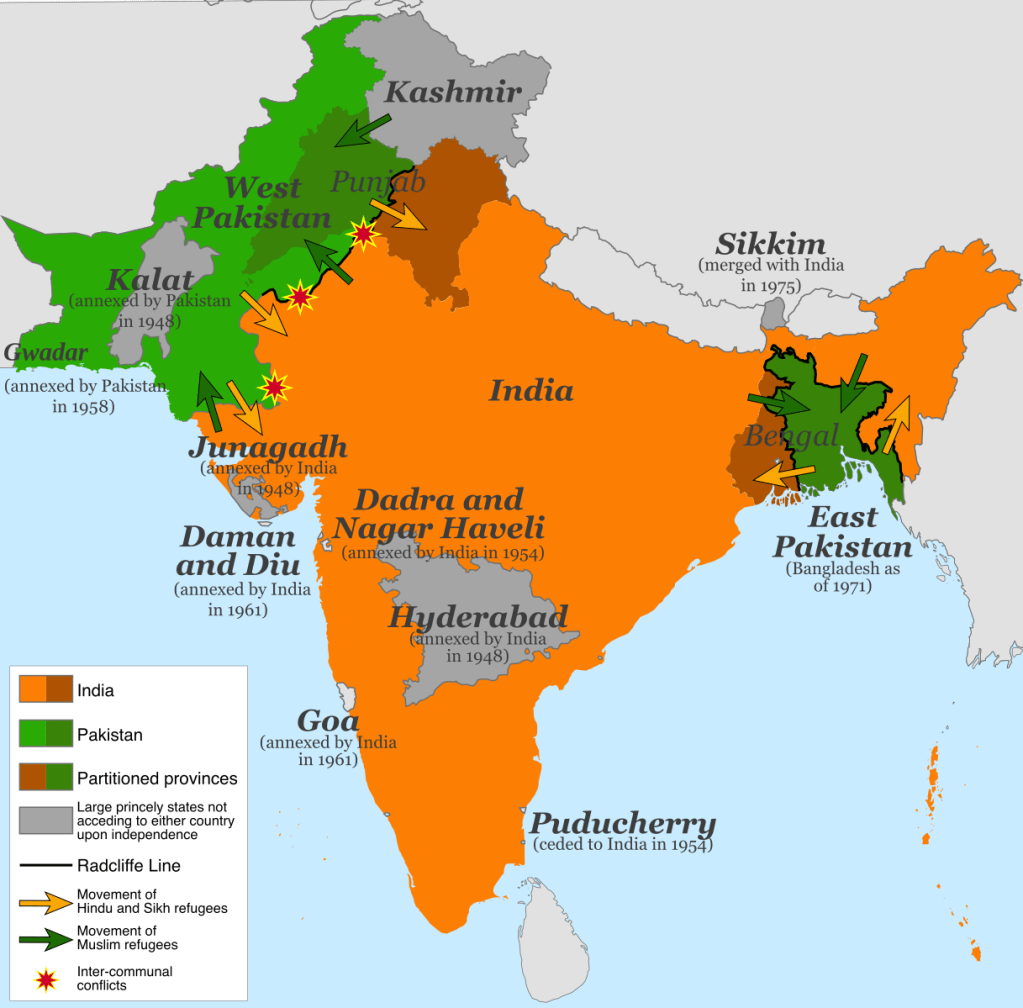

Drawing the Line: The Radcliffe Boundary

With time running out, the British turned to Cyril Radcliffe, a lawyer who had never been to India, to draw the borders — in just five weeks.

The result: the Radcliffe Line, a crude and hurried boundary slicing through two of the most diverse provinces — Punjab in the west and Bengal in the east. Families, communities, and cultures were cut in half overnight.

The Human Cost: One of History’s Largest Migrations

Partition triggered a mass migration of 10–15 million people, as families scrambled to cross into the country that matched their religion.

It wasn’t peaceful. It was horrific.

- Up to 2 million people died in communal violence.

- Women were abducted, raped, and mutilated.

- Trains full of corpses crossed the new borders.

- Villages were emptied of their minorities — a communal cleansing across Punjab and Bengal.

This was not just a political shift. It was a humanitarian disaster.

🔍 Group by Group: What Happened to Each Community

| Community | Beliefs | Main Regions (Pre-Partition) | After Partition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hindus | Polytheistic, Vedic traditions | Most of India, plus Bengal, Punjab, Sindh | Most stayed in India; many fled from Pakistan |

| Muslims | Monotheistic (Sunni, Shia, Ahmadiyya) | Punjab (west), Bengal (east), Kashmir, UP | Became majority in Pakistan; many remained in India |

| Sikhs | Monotheistic, martial and spiritual traditions | Punjab (Lahore, Amritsar, Rawalpindi) | Targeted in Punjab violence; fled to Indian Punjab |

| Christians | Belief in Jesus Christ (Catholic/Protestant) | Kerala, Goa, Bengal, Tamil Nadu | Mostly unaffected; remained in both countries |

| Jains | Non-theistic, follow Ahimsa | Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra | Remained in India |

| Buddhists | Teachings of Buddha | Ladakh, Bengal, North-East | Mostly stayed in India |

| Parsis | Ancient Persian faith (Zoroastrianism) | Mumbai, Gujarat | Stayed in India and thrived economically |

| Jews | Monotheistic | Maharashtra, Kerala | Many later migrated to Israel |

⚖️ Identity Crisis: Sikhs, Hindus and the Law

After independence, India created Hindu personal laws to govern marriage, inheritance, and adoption — but included Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists in that definition.

Why?

To simplify governance by grouping religions with shared cultural roots.

But for many Sikhs, this felt like a denial of their distinct identity. They had their own scripture (Guru Granth Sahib), their own religious practices, and a deep belief in One God — no idols, no caste.

This led to a backlash.

The Sikh Response: We Are Not Hindus

- The Anand Marriage Act (1909) was already on the books to recognize Sikh marriages separately.

- After independence, Sikhs began pushing back — not just legally, but politically.

- The Punjabi Suba Movement led to the creation of a Sikh-majority Punjab in 1966.

- In the 1980s, some called for Khalistan, an independent Sikh state.

Why the Confusion?

1. British Categorisation

The British often treated Sikhs as part of the Hindu fold in early censuses — except when it suited them to classify Sikhs separately for military recruitment. It wasn’t about theology. It was about managing empire.

2. Cultural Overlaps

In real life, many Sikh and Hindu families shared customs, festivals, and even places of worship. This overlap blurred lines — but didn’t erase differences.

3. Hindu Nationalist Claims

Groups like the RSS have tried to portray Sikhism as a branch of Hinduism. But most Sikhs reject this — firmly and vocally.

🧠 Legacy of Partition: Still Felt Today

- India and Pakistan remain in conflict, especially over Kashmir.

- Millions of families carry the trauma of Partition across generations.

- Diaspora communities around the world — including in Australia and New Zealand — still feel the cultural and emotional impact.

Partition didn’t just divide land.

It divided lives, hearts, and histories.

Language Implications

Hindi and Urdu – High mutual intelligibility (in conversation)

- Spoken forms of Hindi and Urdu are very similar, especially in everyday, informal speech.

- They share grammar and basic vocabulary rooted in Hindustani.

- Main differences are:

- Script: Hindi uses Devanagari, Urdu uses Perso-Arabic.

- Vocabulary: Formal Hindi uses more Sanskrit, Urdu uses more Persian/Arabic.

- Result: Hindi and Urdu speakers can usually understand each other very well in casual speech, but may struggle with literary or formal content.

Hindi/Urdu and Bengali – Limited mutual intelligibility

- Hindi/Urdu and Bengali are from different branches of the Indo-Aryan language family.

- Basic vocabulary differs, and pronunciation patterns are quite distinct.

- Script: Bengali uses its own script, different from both Hindi and Urdu.

- Result: Most spoken mutual understanding is limited, unless the speakers have had exposure through:

- Media (Bollywood, music, etc.)

- Shared words or cultural overlap (especially in border areas or among multilingual people)

Summary:

| Language Pair | Can They Understand Each Other? |

|---|---|

| Hindi & Urdu | ✅ Yes, especially spoken/conversational |

| Hindi & Bengali | ⚠️ Not easily, unless familiar |

| Urdu & Bengali | ⚠️ Limited, same as above |

PartitionOfIndia #IndiaPakistanPartition #LegacyOfDivision #IdentityPolitics #SouthAsiaHistory #PostColonialHistory #TwoNationTheory #IndianSubcontinent #MigrationTrauma #DiasporaStories #BritishIndia #HistoricalDialogue #CulturalIdentity #CommunalViolence #RadcliffeLine #PartitionMemory #BLTranslations #LanguageSupport #HistoricalInterpreting #TranslationResource